“The way he stares, he’s forcing you to engage with him.”

Zun Lee, the renowned street photographer known for his profound interactions with his subjects, vividly recalls his encounter with Ekow Nimako, the captivating subject of Ekow’s Helmet.

“It’s not like on Instagram where you look at something for two seconds, and you keep scrolling, he’s like ‘no, you’re going to stay here. You’re going to have a conversation, and you’re not just going to wander off. You’re not just going to shoot a picture and then go.’”

“And then we talked for 30 minutes.”

These types of interactions set Lee apart from image-takers who aimlessly wander the streets of Toronto.

“These people aren’t props… here’s a whole person, not just an object to photograph,” says Lee.

“Doing this forces me to slow down and be more mindful. Hopefully, that will also translate to the people who watch them.”

“It allows for audiences to also then say, hey, ‘what does it mean for me to be in a space?’”

Zun Lee at the Contact Photography Festival

It’s May, and that means it’s photography month in Toronto.

The CONTACT Photography Festival has long been a way for artists to reach broader audiences – amplifying photo exhibitions beyond professional galleries and bringing them out into the cafés and public spaces of the city. CONTACT shines a light on photo art in Toronto.

By giving local photographers a platform to share their work, CONTACT offers worldwide access to the diverse mosaic that is Ontario’s capital city. It’s a space where those behind Canadian lenses can showcase their work – in person or online – to be discovered by the global community. Visitors from across the globe come to attend the festival or exhibit their images, bringing international perspectives to our city.

The festival illuminates individuals like Lee, a physician, educator, and street photographer from Frankfurt am Main who immigrated to Toronto in 1997. Lee wants to demonstrate that it’s not merely the images themselves that are important; it’s the meanings, people, places, discussions, and questions behind them that we must examine. And he’s taking a different approach to achieve these ends.

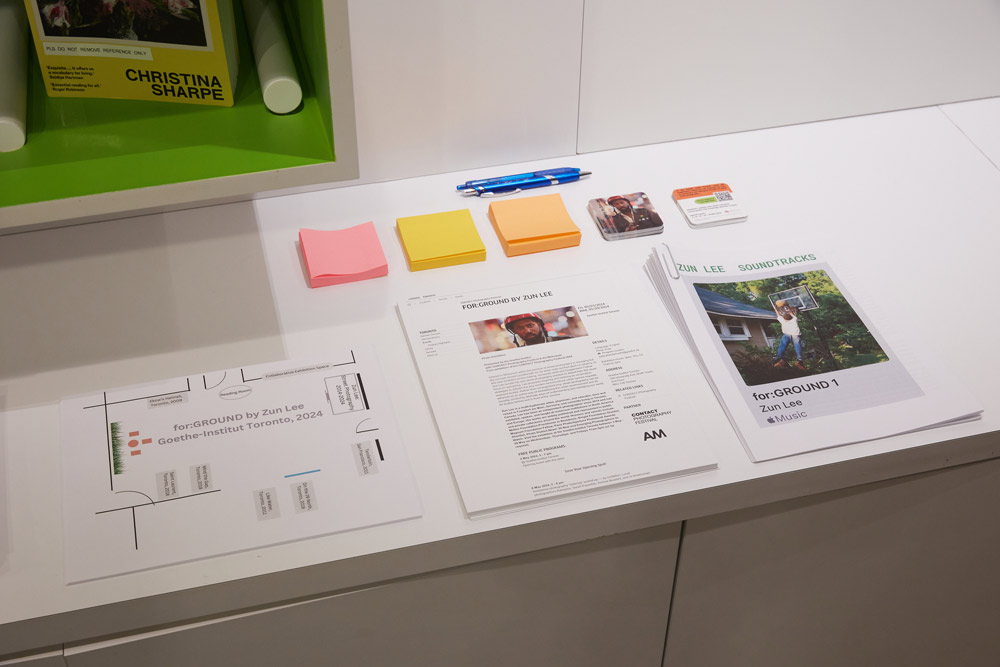

Through a collaboration with the Goethe-Institut and curator Jutta Brendemühl, Lee’s latest exhibition, for:GROUND, opens up a space for conversation rooted in mutual exchange. A goal of the Goethe-Institut is to create a cross-community space that bridges cultures and creates a safe space for debate.

for:GROUND is an offering to Toronto, exploring how people perceive themselves and their bodies in public spaces. Do they feel regulated, threatened, precarious, or at home? “What does it mean to even just move through a certain location,” asks Lee. In essence, what does it mean for a human being to interact with a space, and what questions arise from that interaction? Lee aims to explore why people’s experiences are so varying when public spaces are supposed to be neutral.

Loitering as a reclamation of space

for:GROUND serves as a critique of the rise of flâneurism in street photography – a practice of wandering often dominated by a white-male-centric gaze. In response, Lee utilizes lingering and loitering in public spaces as a way to reclaim space, especially for marginalized communities.

The term loitering traditionally carries with it a negative connotation, one of criminality and over-regulation. Not belonging, not allowed, not welcome. Merely staying in a public space without apparent purpose is viewed as suspicious. You can be fined, pushed out, or forbidden from coming back. And the “luxury” of hanging out in public spaces without intervention is not equal for everyone. Lee’s purpose with for:GROUND is to examine the disproportionate manner in which marginalized and racialized communities are viewed as ”loiterers” in public spaces rather than citizens connecting with each other in oppressive cityscapes.

“If we don’t see it, we can’t talk about it,” says Lee.

Lee also explains that in street photography there’s a sense that BIPOC people cannot do what white flâneurs can do – leisurely wander about and take pictures without being questioned. What are you doing with a camera? What are you doing here, period?

So when Lee hits the public arena, he doesn’t stroll, nor does he wander; he loiters. And it’s opened up a new world of possibilities.

Based on the German cultural concept of Verweilen – meaning dwelling and appreciating the space you’re in – Lee is reclaiming his space and inviting others to do the same.

Zun Lee’s approach to the streets

“I want my images to be intimate and not just kind of stolen, or what people call candid.”

Lee’s loitering practice allows him to connect with subjects more deeply. When hurrying along in a daily routine, it’s challenging to learn about people or see the world through their eyes. But when you stop, look, and listen, you can discover new things about someone that perhaps you’ve always wondered. You can see them.

By staying put and being seen, he’s allowing himself also to be vulnerable, present in the moment, grounded, rather than hunting for the next shot.

“It forces you to really develop a relationship with the city in that very moment and stay in that moment,” says Lee.

It gives him an appreciation of the city and the people in it, and makes him feel more connected, a feeling he hopes others will gain from his photographs.

“I hope the images are not just for the sake of the images.”

Sometimes he’ll repeatedly go to the same spot, stay for a few hours, and not take any photos. He’ll simply notice the same people who occupy the space he’s in and become part of that space himself. And a different relationship then emerges.

“It requires an investment, right, of time, of energy, and just even making yourself visible to others, and not just kind of stealing a shot… You’re not hiding who you are and what you’re doing.” He says this can open the chance for the next encounter to be even more intimate.

The practice also serves Lee, who has struggled with belonging and identity, feeling too much in some places and not enough in others. As someone who sometimes wrestles with isolation and what it means to be a Torontonian, the project has been a way for Lee to reconnect not only with the city but with himself.

“I want you to look at these images, not just as images of somebody or something else, but a way for you to also examine your own relationship to space, to Toronto.”

Lee has an insider/outsider perspective, having come from West Germany but also having lived here long enough to have memory and history in this place. This allows Lee to view Toronto through a unique lens, a situation he says is familiar to many Torontonians.

Lee wants to draw attention to the issues in this city, especially the inequitable access to public space, gentrification, social precarity, racism, and marginalization. Part of Lee’s message is to start talking about these issues, have conversations, and ask questions.

Lee aims to foreground those often viewed as invisible by broader society – older women, the LGBTQ+ community, differently-abled people, and unhoused individuals. Whether that’s owning their corner of Bloor and Bathurst or navigating their daily routines, Lee wants people to realize that everyone deserves to be seen. If nothing else, Lee hopes his photos will make individuals more empathetic to those they see on the streets.

“He is very generous, and it feels like the entire world is a level playing field to him,” says Brendemühl. He’s working to “empower people to reconstitute their Toronto,” with images that help people realize this is their city.

As Brendemüh puts it, “Zun manages to give us perspectives outside of our own experiences.” He portrays communities and people that many Torontonians don’t have access to, don’t intersect with, or simply ignore. When we move around public spaces, we must see it from our own viewpoint, but through this exhibition, Lee helps us learn to see the world through other perspectives.

for:GROUND

The for:GROUND project is a living, moving, developing “exhibition in the making,” says Brendemühl, dedicating one of its walls to ongoing contributions from local and emerging photographers such as Kalmplex, Sarah Espedido, Ammar Bowaihl, and isi bhakhomen. Lee and Brendemühl say these will add something to the conversation.

The exhibition will host a panel of Black arts workers, curators, and artists from Berlin to internationalize the concept of racialized wayward bodies being regulated in public spaces. There will also be a one-on-one portfolio review for TMU photography graduate students.

for:GROUND also features carefully curated playlists, a film screening, Lee’s influential book list, and a sticky note message board for visitors to leave comments, ask questions, and contribute to the conversation.

“We all care about this space. Deeply but differently.” – Zun Lee

for:GROUND runs from May 3-29, 2024, at the Goethe Space in Toronto.

The post The Ground We Share appeared first on Spacing Toronto.