Premier Doug Ford’s sudden and arbitrary interference in the 2018 Toronto municipal election – and the preliminary court decision that allowed him to proceed with it – was a startling reminder of just how powerless Canada’s municipalities are in the face of their provincial governments.

That court case is currently being argued in full at the Court of Appeal of Ontario, and it seems like a good time to revisit the question of municipal government and the Canadian constitution, and what, if anything, could be done to strengthen the status of municipal government and local democracy.

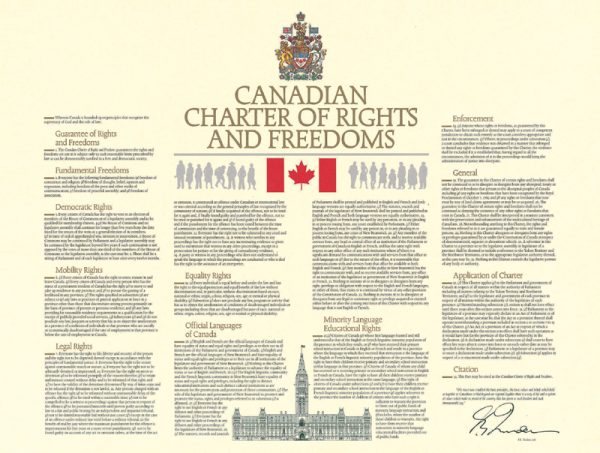

It’s long been understood that Canadian cities are completely under provincial control, as specified in section 92(8) of the Constitution, written at Confederation in 1867: “In each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws in relation to … Municipal Institutions in the Province”. But the court case suggested that local governments do not even benefit from the most basic protections of the Canadian constitution, such as the right to vote (s.3 of the Charter of Rights).

As Toronto historian Jamie Bradburn revealed in a 2014 article on the history of municipal voting in Toronto, it wasn’t until 1972 that Torontonians benefitted from a truly universal franchise, where every citizen over 18 could vote regardless of property qualifications, even though the franchise had been universal at the provincial and federal levels for decades by then. If the preliminary court decision on Ford’s interference in the election holds up, it could conceivably mean that the province has the ability to re-impose property restrictions, or other restrictions, on who could vote in city elections.

It doesn’t stop there, however. As there is no constitutional right to municipal government, there is no legal reason why the province could not arbitrarily abolish elected municipal government, and instead impose a superintendent to run a city, or all cities, in the province. Or it could do away with city government wholesale and run cities through a ministry. It’s notable that some provinces have done that with school boards, and cities have no more constitutional standing than school boards do.

No-one has been overly worried that these scenarios would play out in the past because it seemed like they would be politically disastrous. But Ford’s electoral interference shows that these moves aren’t as unthinkable as one might imagine.

It’s fair to say, I think, that most Canadians expect and want to have an elected local level of government. In fact, it’s likely most Canadians assume it’s one of their democratic rights, and would be shocked to have it taken away or restricted.

Yet one can imagine a scenario where a provincial government vilifies a city council that it finds politically irritating – perhaps a council that is somewhat dysfunctional or corrupt, or perhaps just in a city that is not popular with the rest of the province – and then seizes control of it. A similar thing happened on the other side of the border, for example, where the state government of Michigan seized control of the City of Detroit’s finances in 2013.

So that raises the question, should the Constitution be updated so that the right to a local level of government – and the right to vote for a local government – are constitutionally protected?

A relatively straightforward solution would be to amend s.3 so that it applies to all elected governments in Canada. That would protect the right to a universal franchise in municipal elections, and perhaps protect municipal elections from arbitrary interference. Such a solution could even be done directly between Ontario (presumably with a different party in power) and the feds. However, it would not protect the actual existence of municipal governments, which could still theoretically be abolished.

There’s also a movement to establish Toronto as a “charter city”, possibly with rights and powers protected by a constitutional agreement directly between Ontario and the federal government. The city charter concept is derived from medieval Europe, where many cities acquired specific rights for themselves (both political and economic) in agreements with the monarch. In Canada, the idea is that Toronto could benefit from specific rights in a constitutional amendment directly between the federal and Ontario governments. While it would only require the agreement of those two governments, it could also be dissolved if those two governments decided they no longer wanted it. And it would not protect other local governments in Canada.

To really address the underlying issues would require a full constitutional amendment recognizing a right to a local level of government across Canada. Creating such a constitutional right would be a much more complicated process. I can think of a few questions would need to be addressed, and no doubt there are other questions I haven’t thought of.

First, do all Canadians actually enjoy an elected local level of government? I’m not even sure whether that’s the case. If not everyone has local government, that obviously makes creating a constitutional guarantee more complicated

There’s also the issue of First Nations governments, which have a different set of powers to municipal governments – they both have less power, in some ways, since they are constrained by the outdated Indian Act, but at the same time have a more significant role since they represent a First Nation rather than simply a local level of government. Their existence is often already protected by treaty. Would they be included in constitutional protection of local government? Would they even wish to be?

There’s also the issue of how much the powers of local government would be specified in the constitution. Any amendment would need to specify some powers, otherwise it would be little more than window-dressing.

Specifying areas of revenue that local governments had the right to might not be too difficult. It’s a well-established custom in Canada that all municipalities collect taxes based on the value of property owned in their jurisdiction (although that does not apply to First Nations). Also, all municipalities collect fees for services (such as garbage, water/sewage, and parking). The right to set and collect these taxes and fees could be embedded as part of a constitutional right to local government.

Is that even worth bothering with? The fact is, again, that provincial governments could remove these rights if they want. After all, under the government of Mike Harris in the 1990s, Ontario removed the right of school boards to set and collect their own property taxes for education, instead making it a provincial process. There’s nothing at the moment to stop a province doing that with municipal property taxes too.

It would be much more difficult to define areas of responsibility. Many of the responsibilities of local governments also have a strong provincial government role. Provincial governments set rules and regulations that govern building, zoning, traffic, policing, firefighting, and many other areas that are implemented by local governments. They would be unlikely to give up such powers, and no constitutional amendment can pass without the agreement of most provinces. Yet a constitutional right to local government that didn’t specify areas of responsibility would be meaningless.

Parsing what, exactly, are the current customary bounds of municipal government responsibility that could be unambiguously embedded in the constitution would be the most challenging part of establishing a constitutional right to local government.

An even bigger challenge, of course, would be political. It’s hard to imagine provincial governments wanting to put a lot of effort into a project that would constrain their powers, even if it was limited to recognizing those that local governments already in effect wield.

Nonetheless, it might be worthwhile to start exploring what such a constitutional amendment might look like. Perhaps experts in constitutional law, municipal governance, and other relevant areas could get together and hash out potential scopes and wordings for such an amendment.

It would be, at the least, a useful exercise in clarifying what we actually want and expect from local government, and how much we actually value it. But beyond that, it would be a step towards recognizing formally a right to run local affairs through an elected local government that most Canadians take for granted, value, and would not want to lose.

The post Embedding municipal government in the constitution appeared first on Spacing Toronto.